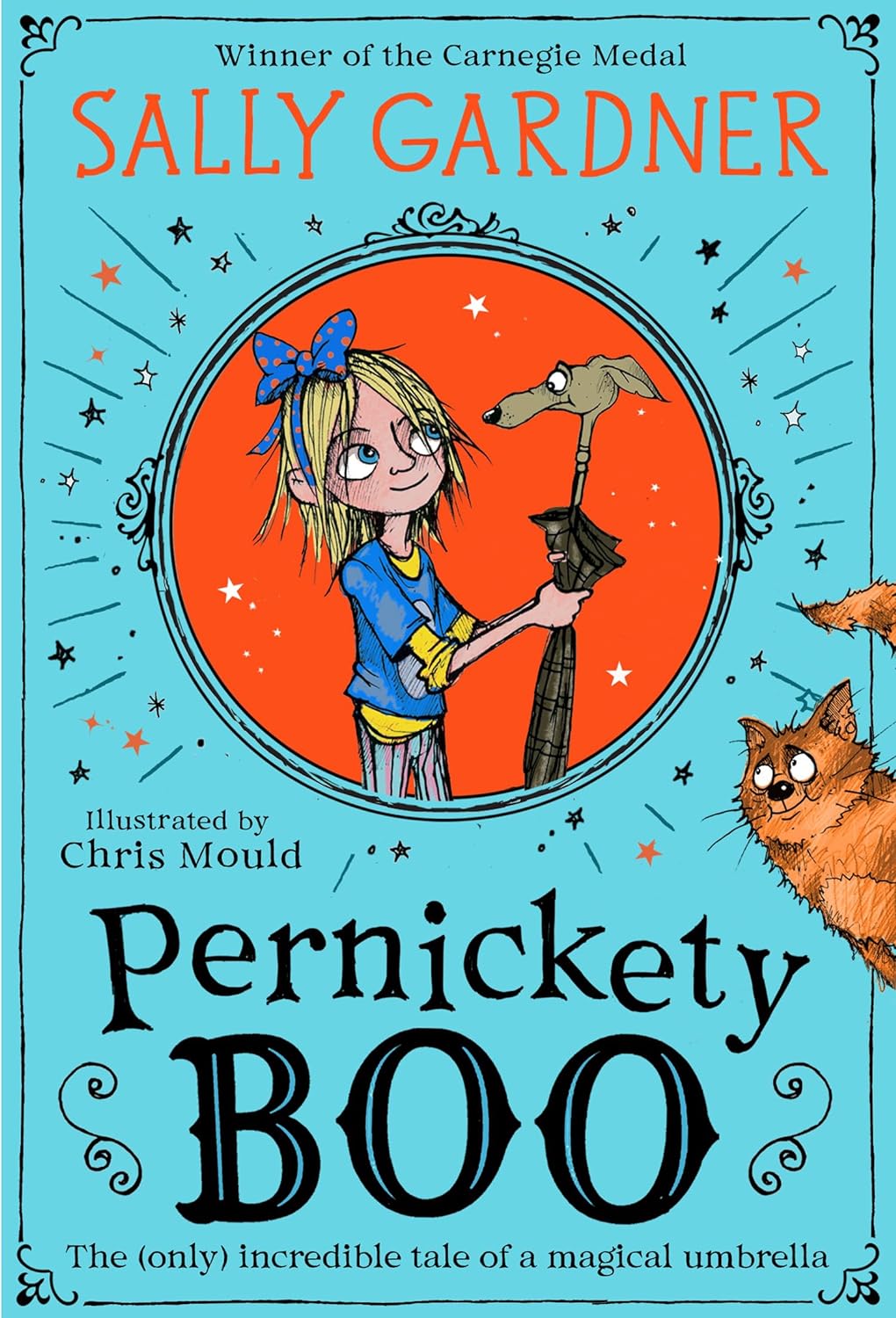

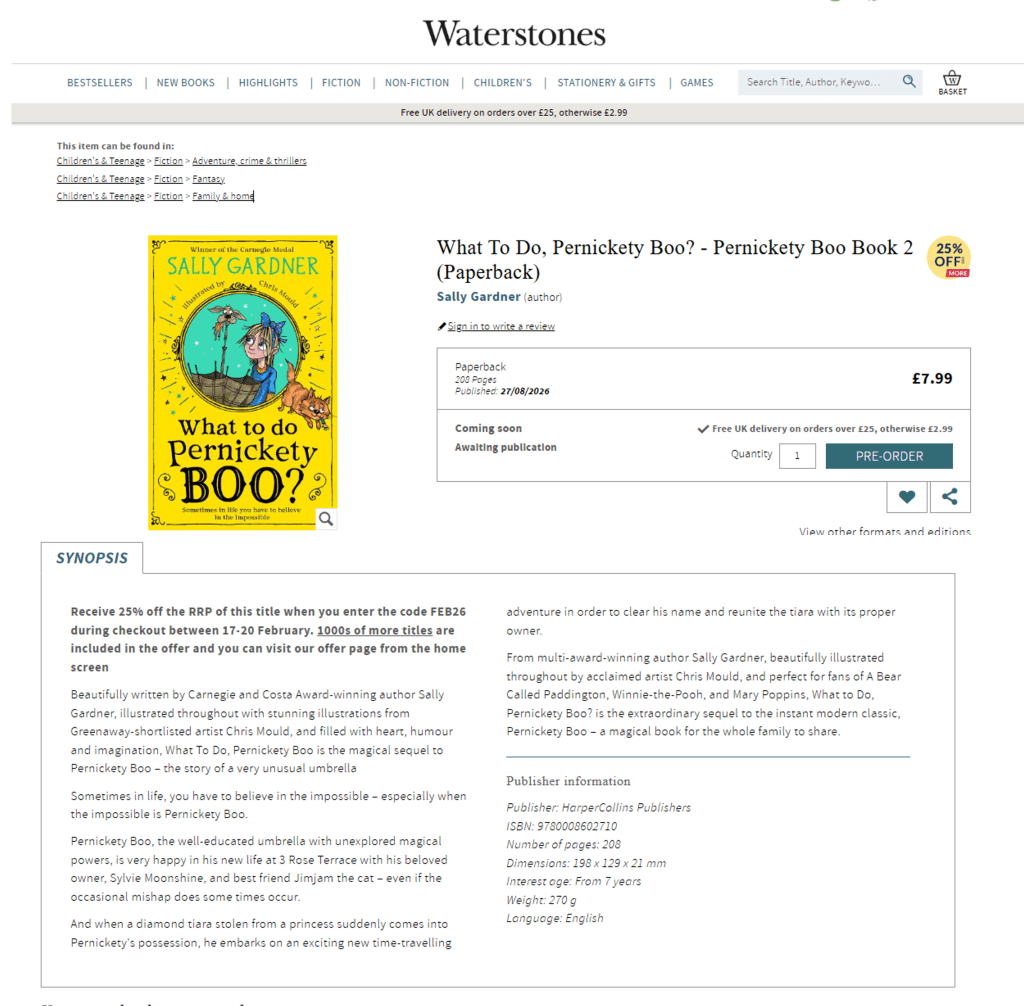

I’m so delighted to share a little secret before What to Do, Pernickety Boo? arrives on shelves. For a very short time, you can pre-order the book with an exclusive 25% discount – a small thank you to readers who love discovering stories early.

From 07:00 on Tuesday 17 February until 23:59 on Friday 20 February, you can receive 25% off the recommended retail price by entering the code FEB26 at checkout.

The offer is available exclusively through the Waterstones website and the Waterstones app, and it’s open to all customers – so whether you’re buying for a child, a classroom, a grandchild or simply for the joy of reading aloud, this is the moment.

What to Do, Pernickety Boo? is a story about finding your place in the world, even when you feel a little different. I can’t wait for it to find its way to you.

Remember to use the code FEB26 – and don’t miss the deadline.